A Rare Case of Insect Wing Pollination

Little is known about Azalea pollination, and in this case, Flame Azalea, or Rhododendron calendulaceum. Wing pollination is especially rare, so this was an exciting concept to illustrate! Based on data from a study by biologist Mary Jane Epps, started in 2012, on Azalea pollination in the Appalachian mountains.

Thanks to The North Carolina Arboretum National Native Azalea Collection curator Carson Ellis for pointing me to MJ’s research and for consulting on all things azalea.

From the copy:

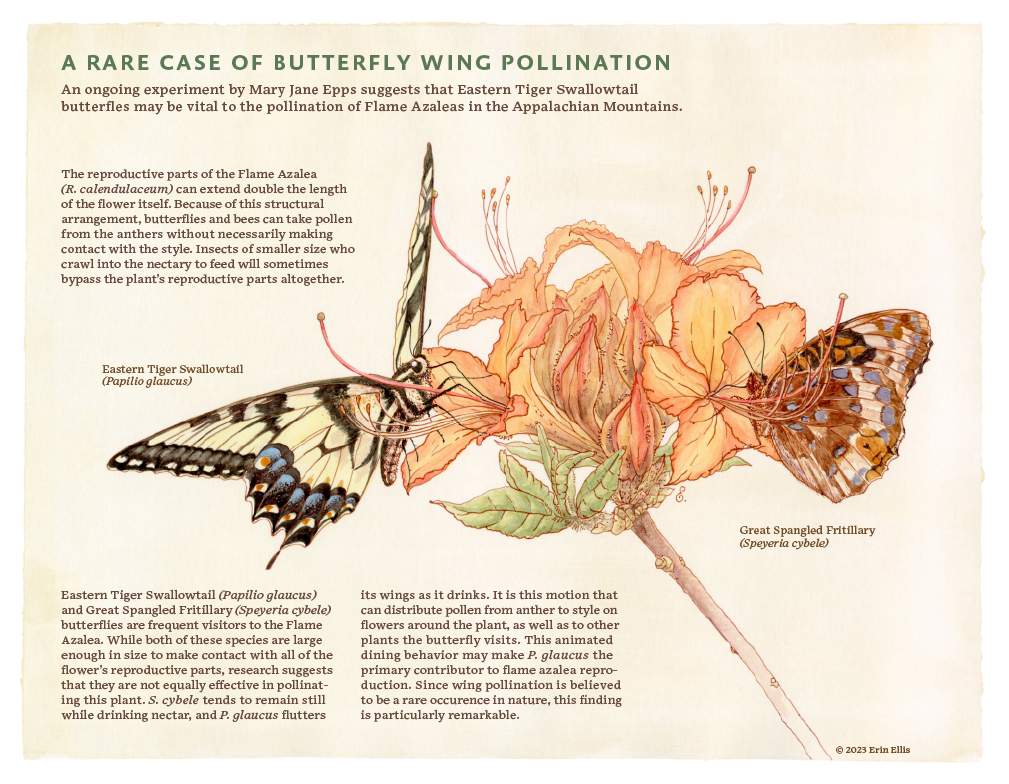

The reproductive parts of the Flame Azalea (R. calendulaceum) can extend double the length of the flower itself. Because of this structural arrangement, butterflies and bees can take pollen from the anthers without necessarily making contact with the style. Insects of smaller size who crawl into the nectary to feed will sometimes bypass the plant’s reproductive parts altogether.

Eastern Tiger Swallowtail (Papilio glaucus) and Great Spangled Fritillary (Speyeria cybele) butterflies are frequent visitors to the Flame Azalea. While both of these species are large enough in size to make contact with all of the flower’s reproductive parts, research suggests that they are not equally effective in pollinating this plant. S. cybele tends to remain still while drinking nectar, and P. glaucus flutters its wings as it drinks. It is this motion that can distribute pollen from anther to style on flowers around the plant, as well as to other plants the butterfly visits. This animated dining behavior may make P. glaucus the primary contributor to flame azalea reproduction. Since wing pollination is believed to be a rare occurence in nature, this finding is particularly remarkable.